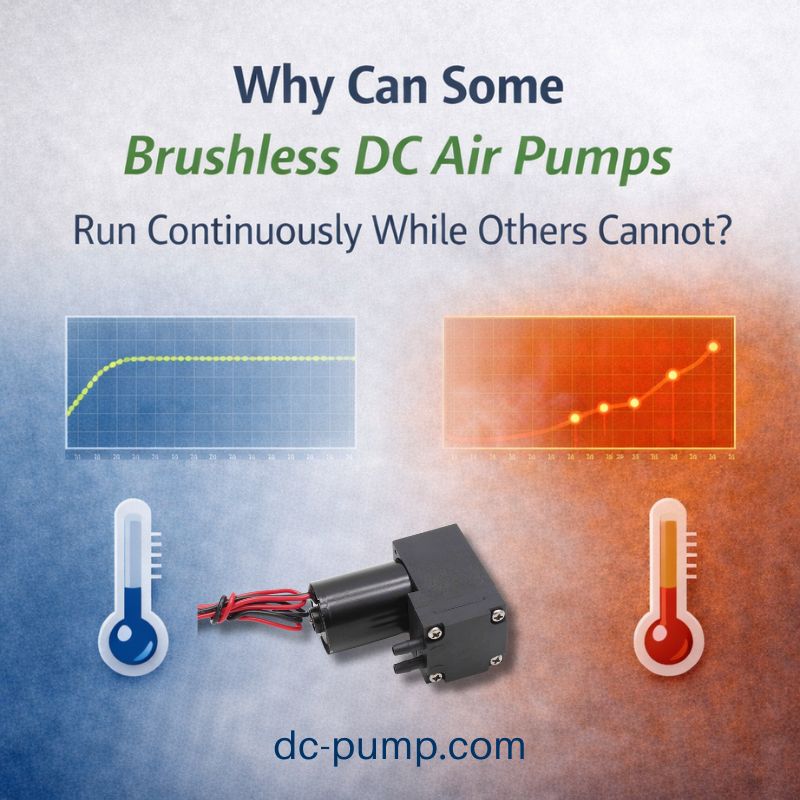

Your device passed every test, but now it’s failing in the cold-soak chamber. The vacuum pump stutters, whines, or won’t start at all, putting your project schedule at risk.

Yes, a DC vacuum pump can start at –20°C, but only if it’s specifically designed for low temperatures and supported by a robust power supply. The cold dramatically increases internal friction, requiring significantly higher startup torque and current from the motor and PCB.

I’ve seen this exact scenario derail projects. A team designs a device for outdoor or refrigerated use, selects a pump with a –20°C operating range on its datasheet, and assumes they’re safe. Then, validation testing begins, and the cold-start tests fail catastrophically. The datasheet provides a number, but it doesn’t explain the physics of why cold is so challenging. Let’s break down what’s happening inside that pump when the temperature plummets and how to design for success from the start.

Why Do Low Temperatures Drastically Increase the Pump’s Startup Load?

Your pump motor seems to be physically “stuck” in the cold. It hums or buzzes but can’t get moving, making you suspect a mechanical failure.

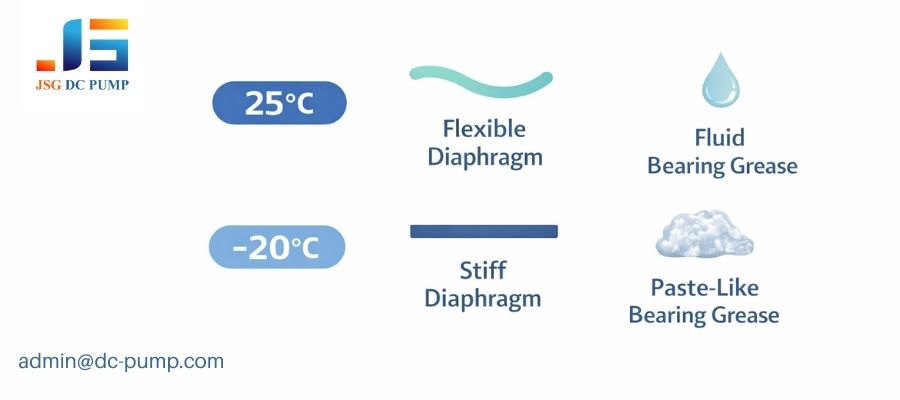

Cold temperatures cause lubricants to thicken like paste and rubber components like diaphragms to stiffen. This massively increases the internal “stiction” or static friction that the motor must overcome to begin the first stroke.

From my 22 years of experience, this is the most underestimated aspect of cold-temperature design. Engineers tend to focus on the electronics, but the root cause is often pure mechanics. The motor isn’t just starting; it’s fighting against a system that has become rigid and resistant.

The Impact of Cold on Internal Components

- Lubricant Viscosity: The grease in the bearings and on mechanical linkages goes from a slippery fluid to a thick, waxy solid. The motor must exert immense force just to shear through this solidified grease. Think of trying to stir honey that just came out of the refrigerator.

- Diaphragm and Seal Hardening: The elastomers used for diaphragms and seals lose their flexibility. At room temperature, they bend easily. At –20°C, an EPDM diaphragm can become over 10 times stiffer. The motor must now literally force this stiff rubber to bend, adding a huge load before any vacuum is even generated.

| Component | Behavior at 25°C (Room Temp) | Behavior at –20°C (Cold Start) |

|---|---|---|

| Bearing Grease | Fluid, low friction | Thick paste, high stiction |

| Diaphragm | Flexible, easy to move | Stiff, requires high force to bend |

| Startup Torque | Normal | Significantly Higher (2x – 5x) |

How Does Cold Affect the Motor and Electrical System?

Your system inexplicably resets or its fuse blows only during cold starts. The power supply works perfectly at room temperature, leading to frustrating and confusing debugging sessions.

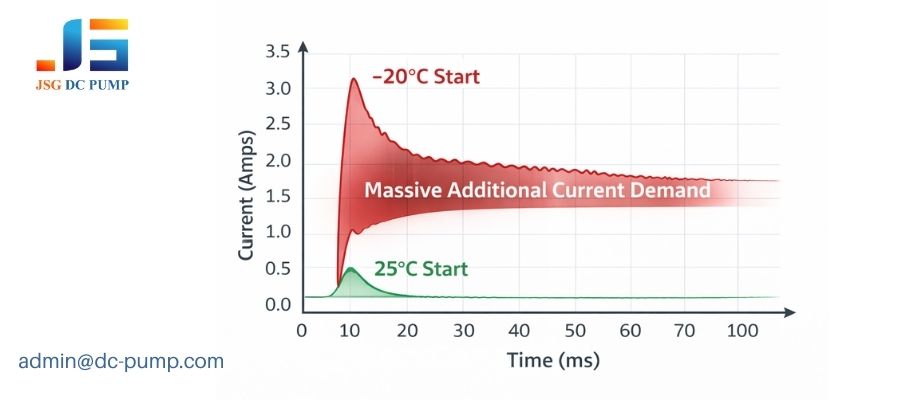

To overcome the high mechanical load of a cold start, the motor must draw a massive inrush current. A standard power supply or a PCB with a strict current limit will interpret this surge as a fault, starving the motor or shutting down completely.

This is where the mechanical problem becomes an electrical one. The physics are straightforward. In a DC motor, torque is directly proportional to current. To generate the enormous torque needed to break the cold stiction, the motor will try to draw a proportionally enormous amount of current from the power supply. A pump that draws 500mA during a normal start might demand 2.5A or more at –20°C. If your PCB is designed to limit current to 1A, the startup will fail every single time. It’s a critical system-level mismatch. The power circuit isn’t designed to handle the demands the cold mechanics are placing on the motor. I’ve often had to advise clients to redesign their power stages specifically to allow for this brief but massive current peak.

Why Is a Standard DC Vacuum Pump Not Suitable for Low Temperatures?

You chose a pump with good specs, but it’s failing in the cold. You’re wondering what makes a “low-temperature” pump different and why you can’t just use a standard model.

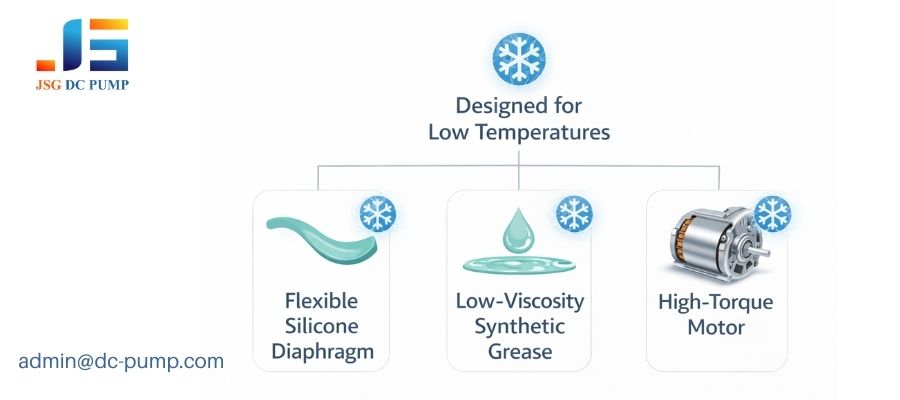

Standard pumps are not designed for cold starts. They use lubricants that solidify and elastomers that harden at low temperatures. A true low-temperature pump uses specialized materials and design choices that are optimized to remain functional in the cold.

When we at JSG DC PUMP design a pump for low-temperature applications, we are making very deliberate engineering choices. It’s not just about a label on a box; it’s a completely different bill of materials and design philosophy.

Key Design Differences

- Specialized Lubricants: Instead of standard lithium grease, we use synthetic, silicone-based lubricants. These are engineered to maintain a low viscosity and provide effective lubrication even at –40°C or below.

- Cold-Resistant Elastomers: We replace standard EPDM or NBR diaphragms and seals with silicone-based alternatives. Silicone rubber retains its flexibility at much lower temperatures, dramatically reducing the startup load.

- Higher-Torque Motors: We often pair the pump head with a more powerful motor than would be necessary for room-temperature operation. This provides the extra torque margin needed to overcome any remaining friction and ensure a reliable start.

This intentional design is the only way to guarantee performance and reliability when the temperature drops. A standard pump is simply not equipped for the challenge.

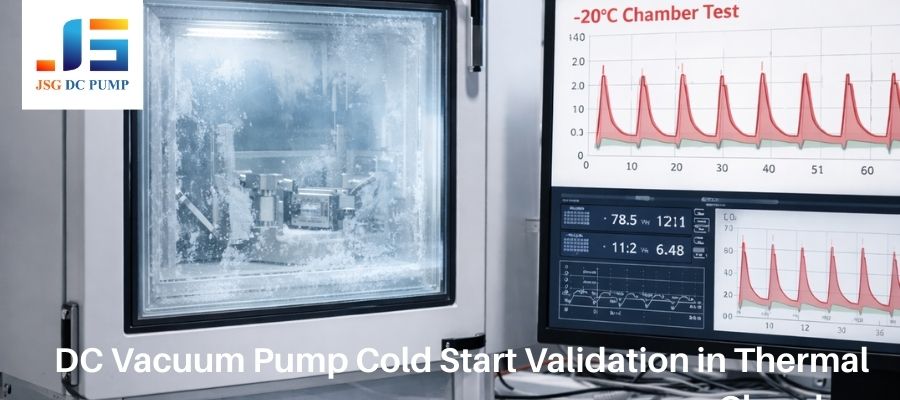

How Should You Test and Validate a Pump for Cold Start Performance?

You need to be certain your device will work reliably in the field. How do you design a validation test that accurately simulates real-world cold-start conditions and exposes potential weaknesses?

Go beyond simple “cold soaks.” Your test protocol must include repeated start/stop cycles, testing under realistic pneumatic loads, and monitoring the electrical current draw during startup. This is the only way to truly validate system robustness.

A common mistake is to cool the device down, turn it on once, and if it starts, mark the test as passed. This is not enough. From my experience helping clients build robust validation plans, here are the essential steps that separate a “pass” from true reliability.

- Extended “Cold Soak”: Ensure the entire device, especially the pump’s core, reaches thermal equilibrium at the target temperature. This can take several hours depending on the device’s mass.

- Pneumatic Load Simulation: Don’t test the pump with open ports. Connect it to the actual tubing, valves, and chambers used in your system to simulate a realistic starting load.

- Power Cycling and Electrical Monitoring: The most critical test. Perform at least 50-100 power cycles (e.g., 10 seconds on, 2 minutes off) while the device is cold. Monitor the inrush current peak and duration for every single start. A reliable system will show consistent electrical behavior. A borderline system will show failures after a number of cycles.

If the pump hesitates even once, the design is not robust enough for production.

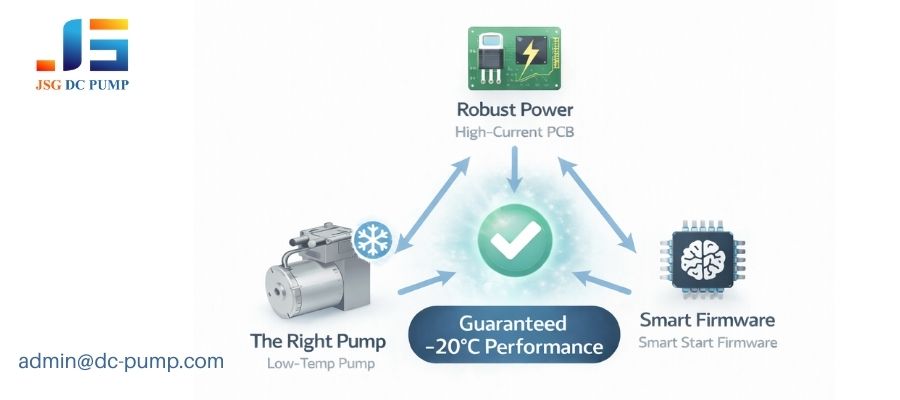

What Is the System-Level Solution to Cold Start Problems?

You understand the pump needs to be special and the PCB needs to be robust. How do you bring it all together into a complete system that works flawlessly in the cold?

The solution requires a three-part strategy: select a pump specifically designed for low temperatures, design a PCB power stage that can supply high transient currents, and implement “smart start” firmware logic to assist the motor.

Solving the cold start challenge is a perfect example of how a component cannot be considered in isolation. The entire system must work in harmony.

The Three Pillars of Cold-Start Success

- The Right Pump: This is the foundation. Start with a pump that uses low-temperature lubricants and a flexible silicone diaphragm. Trying to compensate for a standard pump’s deficiencies with electronics alone is a losing battle.

- The Right Power Supply: Design your PCB power stage to be “permissive” during startup. It must be able to deliver 3-5 times the pump’s rated current for at least 100 milliseconds without triggering an over-current fault. This is non-negotiable.

- Smart Startup Logic (Optional but Recommended): Advanced systems can use firmware to assist the start. For example, the controller can apply a 100% PWM duty cycle for the first 200ms, ignoring speed control, to guarantee the maximum possible current is delivered to break stiction. Once an FG signal confirms rotation, it can then revert to its normal control algorithm.

By combining these three elements, you move from a design that might work in the cold to one that is engineered for guaranteed reliability.

Conclusion

A reliable –20 °C cold start is not a single feature you can “buy” from a pump datasheet. It is the outcome of a deliberate, system-level design strategy—where pump mechanics, power electronics, and control logic are engineered to work together under real-world conditions.

When low-temperature performance is treated as a system requirement rather than a component specification, cold-start failures stop being surprises during validation and field testing. Instead, they become predictable, solvable engineering challenges.

At JSG DC PUMP, we help OEM teams design DC vacuum pump solutions that are validated for low-temperature operation—from pump structure and material selection to PCB power capability and startup control strategies.

If your project requires reliable DC vacuum pump performance at –20 °C or below, contact our engineering team to discuss a system-level solution:

We support OEMs from concept validation to production-ready designs.