You’re chasing higher industrial dc pump efficiency ratings, which feels like the right direction. But in modern industrial equipment, a “high-efficiency” pump alone no longer guarantees a low-energy system.

Emerging trends focus on system-level efficiency rather than just the dc pump. This involves brushless motors, adaptive closed-loop controls, advanced materials, and evaluating performance through Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) instead of just datasheet ratings.

As an engineer who has watched the micro pump industry evolve for over two decades, I see a fundamental shift happening. We’re moving away from a world where component specifications were king. The conversations I have with leading OEM design teams are no longer just about a pump’s peak efficiency. They are about how that pump performs dynamically within their product, under real-world loads, over its entire lifespan. The focus has zoomed out from the component to the complete system, and this changes everything about how we design, select, and measure industrial pumps.

Why Is “System Efficiency” Replacing Standalone Pump Efficiency as a Core Design Metric?

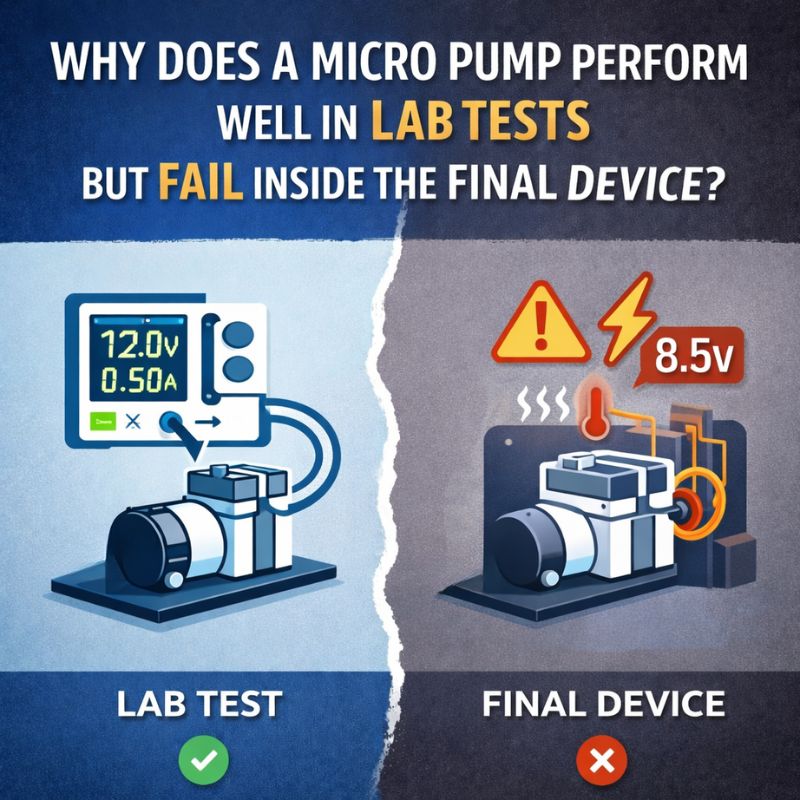

Your team selected a pump with a premium efficiency rating. Yet, the final product’s energy consumption is much higher than expected, causing frustration and design revisions.

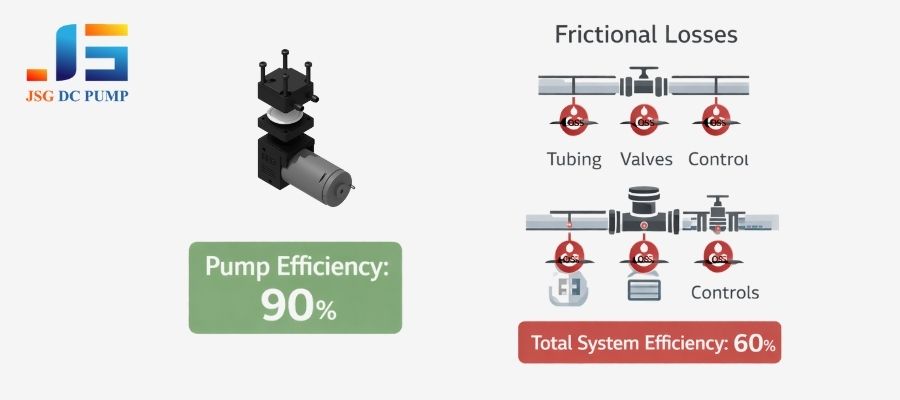

A pump’s rated efficiency, often based on an isolated motor standard like IE3/IE4, is measured under ideal conditions. Real-world system efficiency is dominated by losses in tubing, valves, and running at off-peak load points.

In my experience, this is the most important lesson for modern design teams. For years, we focused on isolated motor efficiency standards. But a highly efficient motor driving an inefficient pump head or fighting against a poorly designed system is simply wasting energy. The industry is waking up to this reality. We are now looking at the entire efficiency chain, which includes every link from the power supply and driver to the pump and the final load. The true goal is to optimize the operating point efficiency—the efficiency at the specific pressure and flow your application actually demands.

This shift in focus can be seen in the table below:

| Metric | Old Approach (Component-Focused) | New Approach (System-Focused) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Increase the efficiency rating of a single component. | Lower the actual energy consumption of the entire system. |

| Key Indicator | Motor efficiency (e.g., IE3/IE4), pump’s peak efficiency. | System efficiency at a specific operating point. |

| Evaluation | Consulting component datasheets. | Testing the entire system under real-world load conditions. |

| Final Result | High theoretical efficiency but potentially high real-world energy use. | Predictable and genuinely low total energy consumption. |

How Are Brushless Motors and Advanced Drives Redefining Energy Efficiency?

You need a reliable pump for a demanding application, but traditional brushed motors wear out or overheat too quickly. You’re searching for a more robust and efficient alternative.

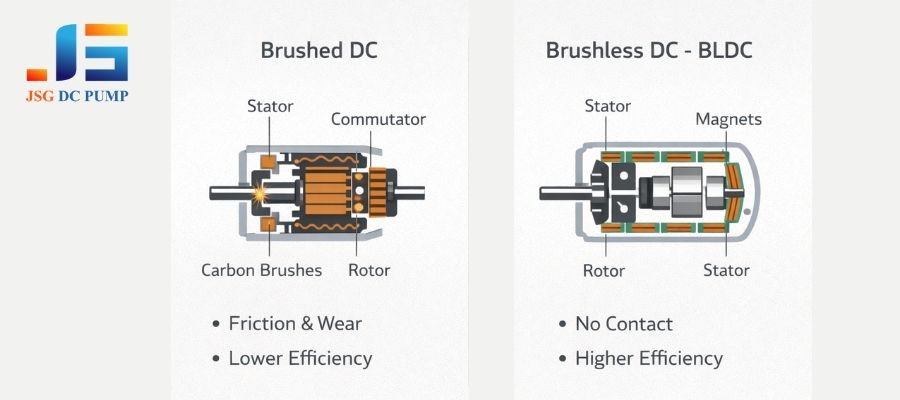

Brushless DC (BLDC) motors are replacing brushed motors as the core of industrial pumps. Their electronic commutation minimizes electrical and thermal losses, dramatically increasing efficiency, lifespan, and stability.

The transition to brushless technology is a massive leap forward for industrial dc pumps. Unlike brushed motors that rely on physical contacts (brushes) that create friction, heat, and wear, BLDC motors are controlled electronically. This offers several core engineering advantages as detailed in the table:

| Characteristic | Brushed DC Motor | Brushless DC (BLDC) Motor |

|---|---|---|

| Commutation | Mechanical Brushes | Electronic Driver |

| Primary Wear Part | Brushes | None (besides bearings) |

| Efficiency | Moderate, reduced by friction. | High, no brush losses. |

| Heat Generation | Higher, with heat in rotor and brushes. | Lower, with heat on the easy-to-cool stator. |

| Lifespan | Limited, often a few thousand hours. | Extremely long, often over 20,000 hours. |

| Best For | Intermittent, low-cost applications. | Continuous duty, high-reliability, and high-efficiency applications. |

This technological shift means longer operational life, less maintenance, and more stable performance under continuous, heavy loads—all critical requirements for modern industrial equipment.

Why Will Load-Adaptive and Closed-Loop Control Become Standard Requirements?

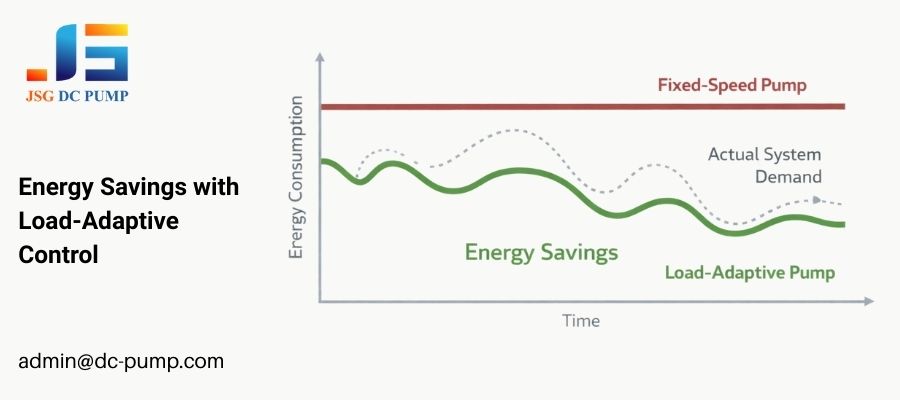

Your pump runs at full speed even when the task only requires a fraction of its power. This wastes energy, generates excess heat and noise, and stresses components unnecessarily.

Load-adaptive pumps use closed-loop control to adjust their speed based on real-time feedback from pressure or flow sensors. This allows the pump to deliver exactly what is needed, dramatically cutting energy use during partial-load conditions.

The era of the “dumb” fixed-speed pump is ending. In the real world, industrial loads are rarely constant. Adopting closed-loop adaptive control offers multiple benefits:

- Significant Energy Savings: Power consumption can be reduced by up to 90% during partial-load or standby periods, as the system only draws energy when needed.

- Reduced Noise and Vibration: The pump runs at high speed only when necessary, creating a quieter operating environment for most of the duty cycle.

- Improved Process Control: Real-time feedback allows the system to precisely maintain pressure or flow setpoints regardless of load fluctuations, improving product quality and consistency.

- Extended Component Lifespan: Lower average operating speeds and reduced mechanical stress significantly prolong the life of the motor, bearings, and pump diaphragm.

For OEM system architects, this means designing for feedback control is no longer an optional feature; it’s a core requirement for building a competitive and intelligent machine.

How Are Material Innovations Improving Efficiency Without Increasing Energy Consumption?

You are trying to improve efficiency, but simply using a bigger motor adds too much cost and power draw. You need a smarter way to reduce the energy required to move fluid.

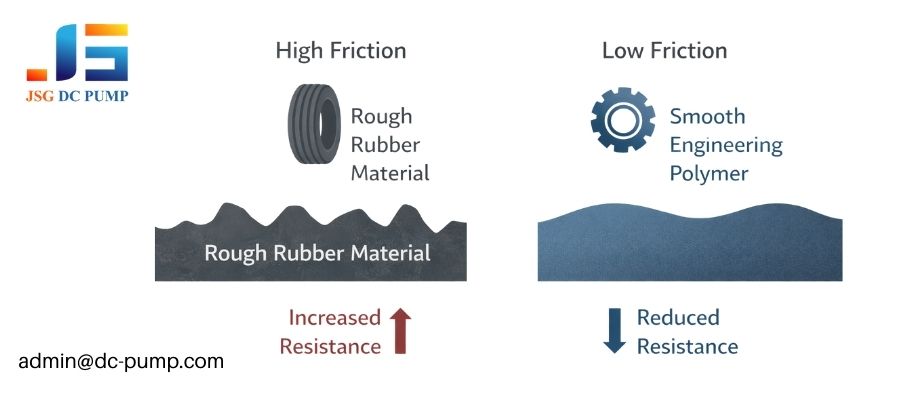

Innovations like low-friction polymers for diaphragms and optimized valve geometries are reducing the internal mechanical losses of the pump. This allows the pump to move more fluid with the same amount of motor effort.

Pure power isn’t the only path to performance. We are seeing major gains from advanced material science. A significant portion of a motor’s energy is spent just overcoming the internal friction and stiffness of the pump’s own components. Here are a few key areas of innovation:

- Diaphragm Materials: We are using specialized engineering polymers for diaphragms. They are not only more durable and chemically resistant but also more flexible and have lower internal friction. This means less energy is wasted with every stroke.

- Valve Geometry: Through fluid dynamics simulation, we can optimize the shape of the tiny internal valves. This reduces turbulence and allows them to open and close with less resistance.

- Housing & Structural Components: Using lightweight, high-strength polymers in place of metal can reduce the weight of moving parts without sacrificing strength, lowering the inertial load the motor needs to overcome.

The goal of these innovations is to improve efficiency retention, ensuring the pump maintains its high performance over millions of cycles, not just when it is new.

Why Is Thermal Management Becoming a Key Efficiency Limiter in Compact Industrial DC Pump Designs?

Your compact device contains a low-power pump, but it still gets surprisingly hot, causing performance to drift over time. You are hitting an invisible thermal wall.

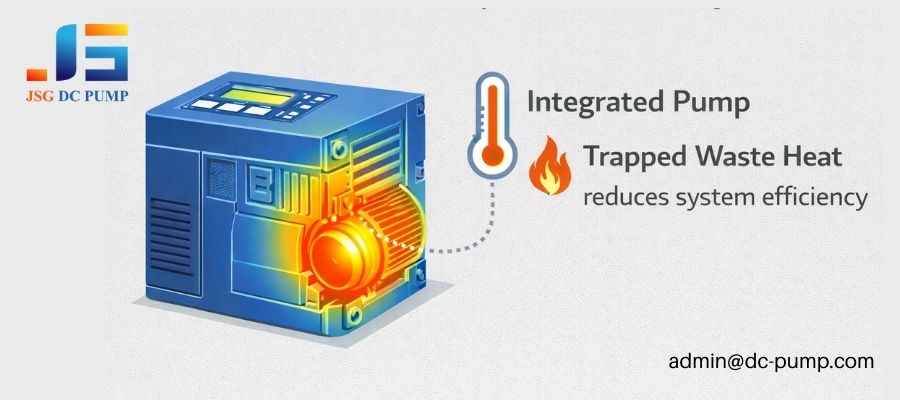

All electrical inefficiency manifests as heat. In tightly packed modern equipment, this heat gets trapped, raising the pump motor’s temperature, which in turn further reduces its electrical efficiency and can lead to premature failure.

This is a real-world problem I see constantly. “Low power” does not always mean “high efficiency.” In fact, heat buildup creates a vicious cycle:

- Electrical Loss Creates Heat: Any inefficiency in the pump’s motor converts electrical energy into waste heat.

- Heat Is Trapped, Temperature Rises: In a sealed enclosure, this heat cannot easily escape, causing the pump’s internal temperature to increase.

- Higher Temperature Increases Resistance: The electrical resistance of the motor’s copper windings increases with temperature.

- Higher Resistance Causes Lower Efficiency: Increased resistance means even more electrical energy is converted into heat instead of mechanical work, reinforcing the cycle and potentially leading to thermal shutdown or burnout.

In compact designs, effective thermal management—such as considering airflow paths, using the chassis as a heat sink, and derating the motor for continuous duty—is now a primary design constraint for ensuring a pump can deliver its rated efficiency and reliability.

How Are OEM Buyers Evaluating Efficiency Through Total Cost of Ownership (TCO)?

Your purchasing department wants the lowest-priced pump. Your engineering team is worried that a cheap pump will lead to high energy bills and costly field failures down the road.

Sophisticated OEM buyers now evaluate pumps based on Total Cost of Ownership (TCO). This calculation balances the initial purchase price against long-term energy consumption, expected maintenance costs, and the business risk of downtime.

The conversation with procurement teams is changing. The focus is shifting from a simple price tag to a much more holistic view of value. The table below compares these two perspectives:

| Cost Factor | Traditional View (Purchase Price-Focused) | Modern View (TCO-Focused) |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Cost | The primary driver of the decision. | Just one part of the total cost. |

| Energy Use | Often overlooked or underestimated. | Calculated as a key component of long-term operating cost. |

| Maintenance | Seen as a future problem. | Estimated and factored into the total cost; low maintenance = lower TCO. |

| Downtime Risk | Hard to quantify and often ignored. | Considered the most critical business risk; high reliability dramatically lowers TCO. |

Therefore, a pump that is slightly more expensive initially but is demonstrably more reliable and energy-efficient often presents a far lower TCO and is seen as the better investment.

How Will the “High-Efficiency Industrial Pump” Standard Be Defined by 2026 and Beyond?

Looking ahead, what will your team need to provide to prove a pump is truly “high-efficiency”? A single number on a datasheet will no longer be enough.

By 2026, a “high-efficiency” pump will be defined by its combination of efficiency, reliability, and intelligent control. Manufacturers will be expected to provide system-level solutions with transparent validation data, not just isolated components.

The future standard for an industrial pump will be a fusion of three core pillars:

- Peak Component Efficiency: It must still be fundamentally efficient in its mechanical and electrical design.

- Lifetime Reliability & Stability: It must sustain that efficiency over its entire operational life with minimal degradation.

- Intelligent, Adaptive Control: It must be able to adapt to system demands to maximize efficiency under real-world, variable loads.

This means the role of the pump manufacturer is changing, as shown below:

| Role Transformation | From (Old Model) | To (New Model) |

|---|---|---|

| Positioning | Component Supplier | System Solution Partner |

| Deliverable | A pump and a datasheet. | An integrated proposal of a pump, driver, and control strategy. |

| Core Value | Price and peak performance. | System-level efficiency, reliability, and transparent validation data. |

Transparency, collaboration, and a deep understanding of system dynamics will be the hallmarks of a leading pump manufacturer in 2026 and beyond.

Conclusion

At JSG DC PUMP, we see our role as more than just a supplier. We are an engineering partner, here to help you navigate these trends and build truly efficient systems.