You assume your new brushless dc air pumps can run 24/7, but it starts failing once installed in the final product. The root cause is rarely the motor type itself. “Brushless” defines how the motor is commutated, not how the pump behaves thermally or mechanically in a real system.

A brushless DC air pump’s ability to run continuously is determined by how effectively it manages heat under load. Motor speed, pressure, airflow, noise, control electronics, and mechanical design all contribute to whether the pump can achieve a stable operating temperature. Observing how different designs handle these factors helps explain why some pumps survive continuous operation while others do not.

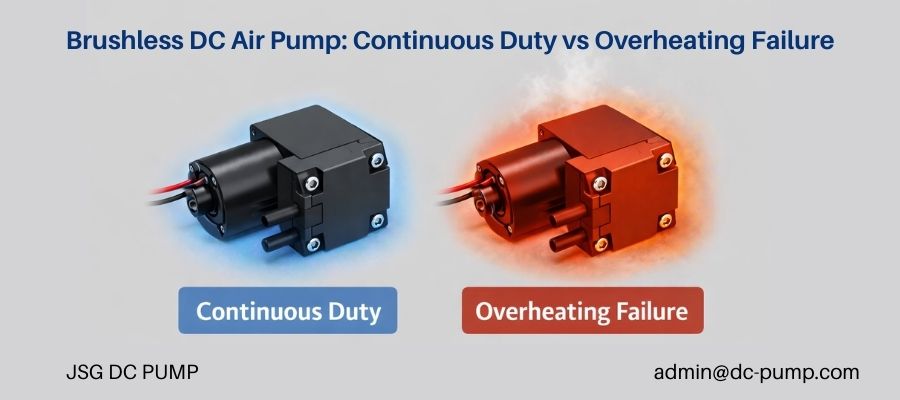

Brushless DC Air Pump Thermal Balance

As an engineer with JSG DC PUMP for over 22 years, I’ve seen that exact scenario play out countless times. A team is excited about a compact, powerful brushless pump, but it can’t survive their real-world, 24/7 application. The frustration is understandable. The key is to realize that “continuous duty” isn’t a feature you buy; it’s a system characteristic you must design for. The factors mentioned above—speed, pressure, heat—are all interconnected. Let’s break down each one so you can see the full picture and learn how to identify a truly robust pump.

What Does “Continuous Operation” Actually Mean for a Brushless DC Air Pumps?

You write “continuous duty” on your spec sheet, but the pump you receive fails. This mismatch happens when the load isn’t defined, leading to costly mistakes and project delays.

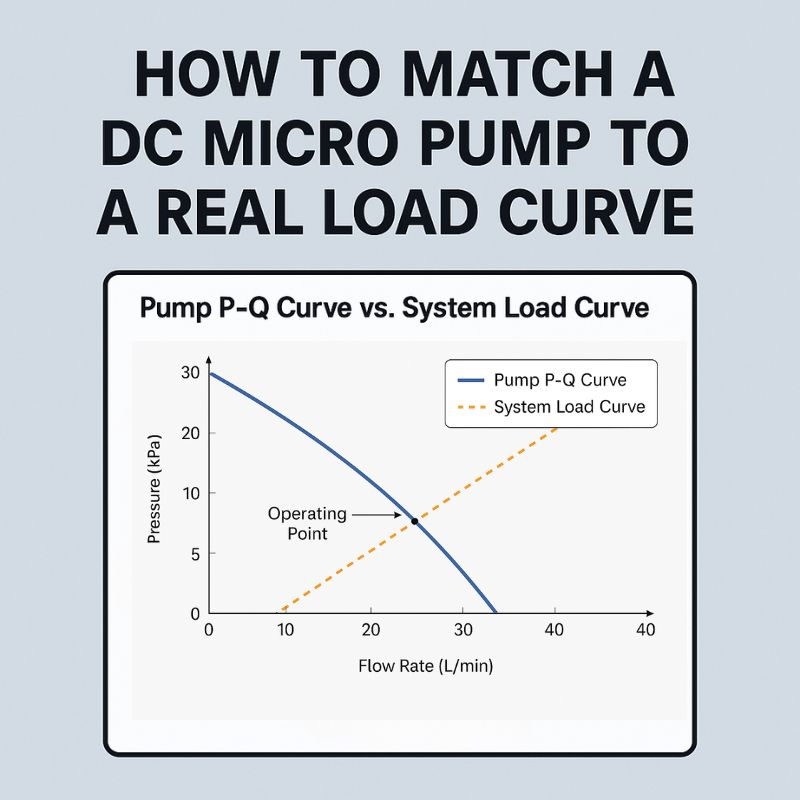

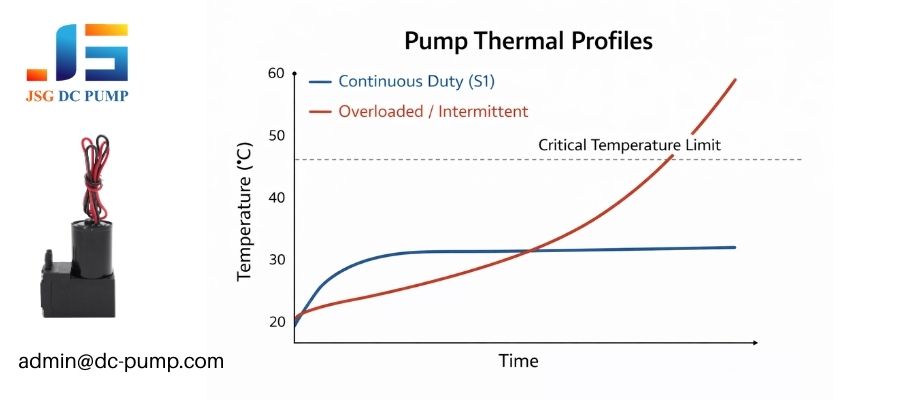

“Continuous operation,” or S1 Duty, means the pump can run indefinitely under a specified load without overheating. This is not the same as intermittent duty, which requires rest periods. Your specified load (pressure and flow) is critical, as a pump’s free-flow capability is irrelevant.

Continuous vs. Intermittent Duty Thermal Profiles

Continuous vs. Intermittent Duty Thermal Profiles

I often get specifications from OEMs that just say “Duty Cycle: 100%,” which is a major red flag for me. 100% duty at zero pressure is easy; it tells me nothing useful. The real question is, “100% duty at what pressure and flow rate?” A pump that can run forever while pushing no air might overheat in just ten minutes when working against its maximum rated pressure. This simple misunderstanding is one of the most common sources of conflict between an OEM’s hopes and a pump’s physical limits. We need to define the work to define the duty.

Duty Cycle Defined by Workload

A pump’s duty cycle rating is only meaningful when it’s tied to a specific job. The thermal stress on the pump changes dramatically with the pressure it has to work against.

| Specification Quality | Example | Why It’s a Problem or Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Vague Spec | “Must run continuously.” | Fails to define the thermal load. The pump will likely fail. |

| Clear Spec | “S1 Duty at 50 kPa & 2 L/min.” | Provides a clear, testable performance target. |

| Intermittent Spec | “10 min on / 10 min off at 80 kPa.” | Clearly defines an intermittent workload for peak tasks. |

Why Does Thermal Balance Determine Continuous-Duty Capability?

Your small brushless pump gets very hot, very quickly. You rightfully worry about its lifespan. The issue is that the pump is generating more heat than it can get rid of.

A pump can only run continuously if it reaches thermal equilibrium, where heat dissipation equals heat generation. If heat builds up faster than it can escape, the pump enters thermal runaway, overheats, and ultimately fails. This balance is the absolute key to continuous operation.

motor windings, bearings, and air compression

motor windings, bearings, and air compression

I like to use a simple analogy: think of a small pump as a bucket with a hole in it. The water pouring into the bucket is the heat being generated. The water leaking out of the hole is the heat being dissipated. If you pour water in faster than it can leak out, the bucket will overflow. This is thermal accumulation, and it leads to failure. A true continuous-duty pump is like a bucket where the hole is big enough to handle the inflow indefinitely. I’ve seen great pumps fail because they were buried in insulation inside a sealed product, effectively plugging the hole in the bucket.

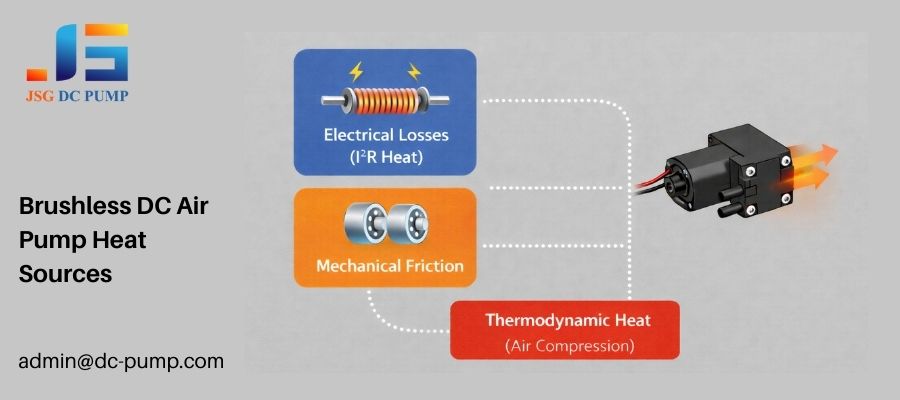

The Sources of Waste Heat

Heat is a byproduct of work and inefficiency. In a DC air pump, it comes from three main places:

-

Electrical Losses: The current flowing through the motor’s copper windings generates heat.

-

Mechanical Losses: Friction from the motor bearings and pump mechanism creates heat.

-

Thermodynamic Heat: Compressing air itself generates significant heat. This is often the largest heat source under load.

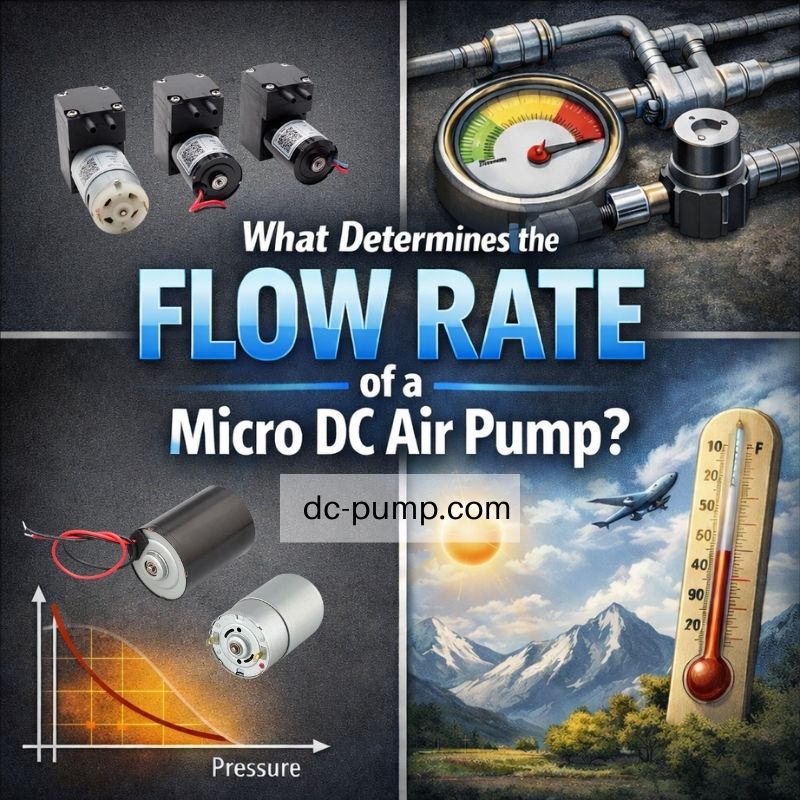

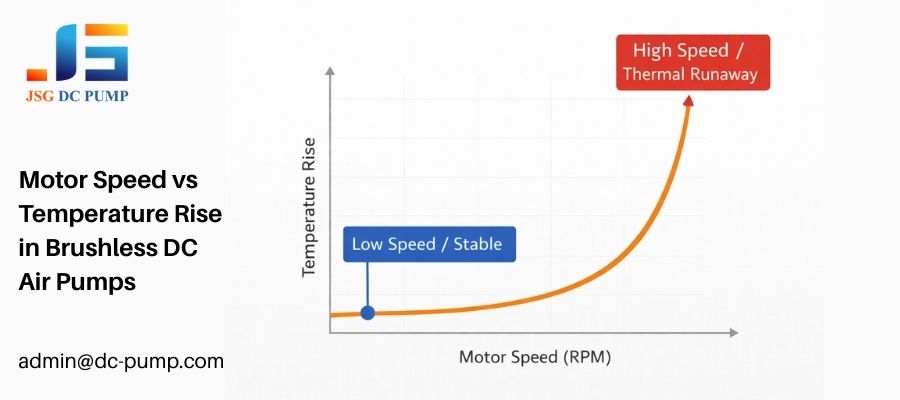

How Does Motor Speed Become the Hidden Limiting Factor in Small Brushless DC Air Pump?

You chose a tiny pump with amazing pressure ratings. But in your testing, it just overheats. The issue is the extreme speed required to get those big numbers from a small package.

To achieve high pressure and flow from a very small pump, designers must use extremely high motor speeds (RPM). This high energy density generates heat much faster than the small pump body can dissipate it, making continuous operation at high loads impossible.

A chart showing the exponential relationship between motor RPM and temperature rise

A chart showing the exponential relationship between motor RPM and temperature rise

I always remind engineers: speed, not voltage, is the real stress factor. A pump at 12V and 10,000 RPM is under far more thermal stress than a larger pump at 12V and 3,000 RPM. A customer once wanted to use one of our tiny pumps for a 24/7 air sampling application. The pump had the perfect flow rate, but it was designed for short-burst use in medical devices, and its high RPM caused it to get hot fast. We guided them to a slightly larger, low-speed model instead. It was quieter, ran cool, and was perfect for their continuous-duty needs. They traded a tiny bit of size for a massive gain in reliability. This is a classic case of high energy density working against you.

| Characteristic | High-Speed Design | Low-Speed Design |

|---|---|---|

| Performance | High Pressure & Flow | Moderate Pressure & Flow |

| RPM | Very High (>5,000 RPM) | Low (<4,000 RPM) |

| Thermal Profile | Heats up very quickly | Heats up slowly, stabilizes |

| Ideal Use | Intermittent, short bursts | Continuous operation |

Why Is Noise a Practical Indicator of Continuous-Duty Potential?

You’re comparing two pumps. One is quiet, the other is loud and whiny. This difference in sound tells you almost everything you need to know about their potential for continuous duty.

Acoustic noise and vibration are direct symptoms of wasted energy and high mechanical stress. A loud, high-pitched pump is inefficiently converting energy into noise instead of airflow. This wasted energy becomes heat, making the pump a poor candidate for continuous duty.

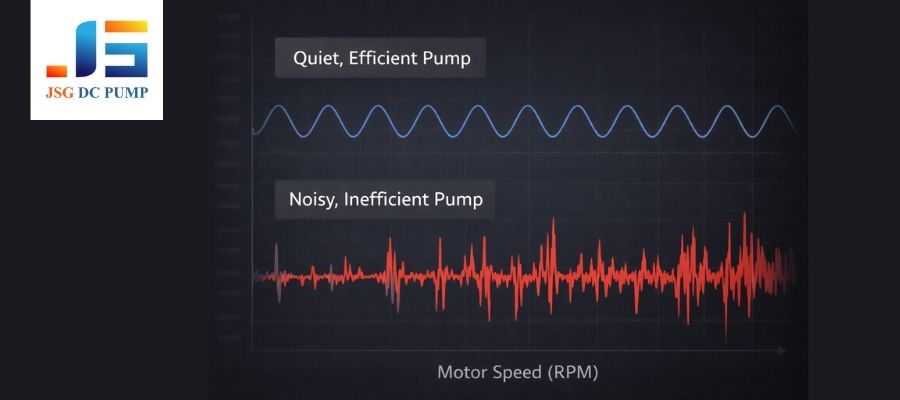

An audio waveform visualization comparing a quiet pump to a noisy pump

An audio waveform visualization comparing a quiet pump to a noisy pump

I use a simple, hands-on test when I visit a client’s lab. I ask them to run the pump on a table, and I just listen to it and feel the vibration. A pump that’s a good candidate for continuous duty will be quiet, with a low-pitched hum and minimal vibration. In contrast, a pump designed for intermittent, peak performance often has a high-pitched, sharp whine and will vibrate noticeably. That sharp noise isn’t just annoying; it’s the sound of high stress and inefficiency. It’s a clear warning that the pump cannot sustain that operating state for very long. The wasted energy causing the noise and vibration is directly converted into heat, which is the ultimate enemy of continuous operation. A quiet pump is an efficient pump, and an efficient pump runs cool.

What Is a Simple Engineering Rule of Thumb for OEM Evaluation?

You need to quickly judge if a pump is right for your 24/7 application. You don’t have time for complex simulations. There’s a practical way to make an accurate initial assessment.

Yes. You can make a solid initial judgment by observing the pump’s speed, noise, and temperature. A pump that is fast, loud, and gets hot quickly is designed for intermittent use. A pump that is slow, quiet, and warms up gradually is a good continuous-duty candidate.

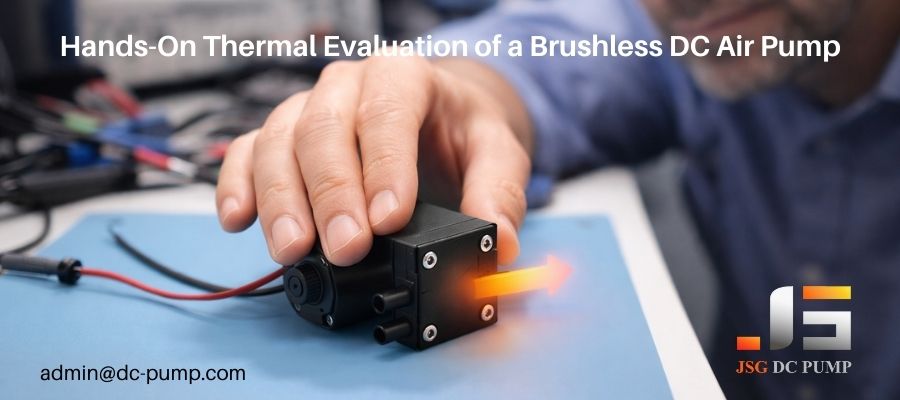

An engineer’s hand feeling the temperature of a running DC pump

An engineer’s hand feeling the temperature of a running DC pump

This is something I teach all our junior engineers. You don’t always need instruments to spot a problem. Use your own senses. Take the pump you are considering and run it on your bench at the target pressure you need. Pay attention. How does it sound? How does it feel? This simple, hands-on test is surprisingly effective and can save you from pursuing a design path that is doomed to fail from thermal issues. It cuts through the marketing claims on a datasheet and gives you a real feel for the pump’s true nature. A pump that gets too hot to comfortably touch within five minutes is almost certainly not a continuous-duty device, no matter its motor type.

Why Do Control Strategy and Drive Electronics Still Matter?

You picked a good low-speed pump, but it’s still running hot. You thought you chose the right hardware. The problem might not be the pump, but how you are controlling it.

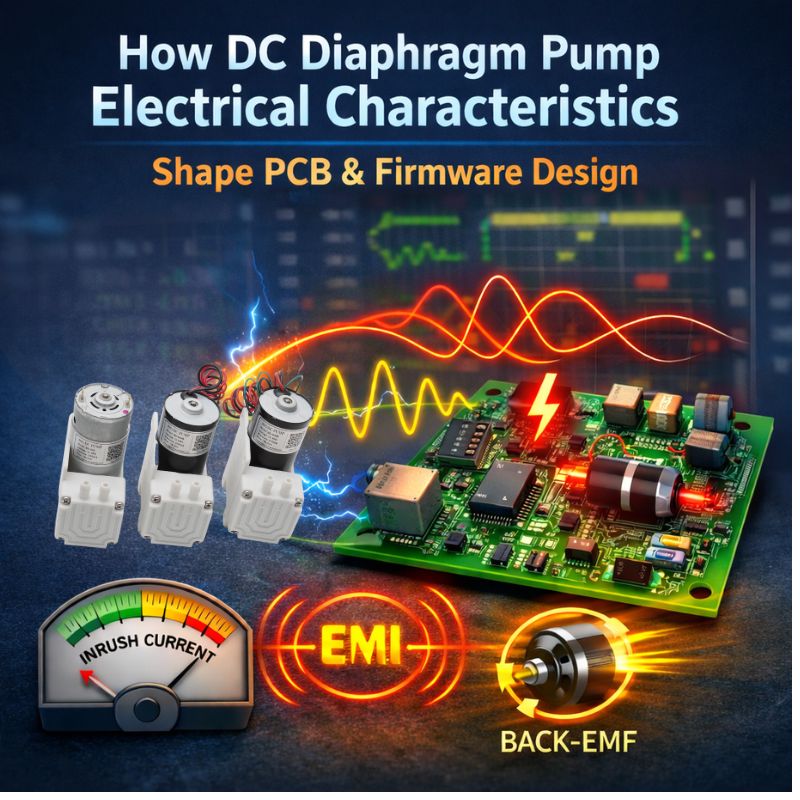

Even a perfect continuous-duty pump can be made to fail with a poor control strategy. The drive electronics and the PWM signal you use directly affect heat generation. An inefficient control signal can increase motor losses and cause overheating, even in a well-designed pump.

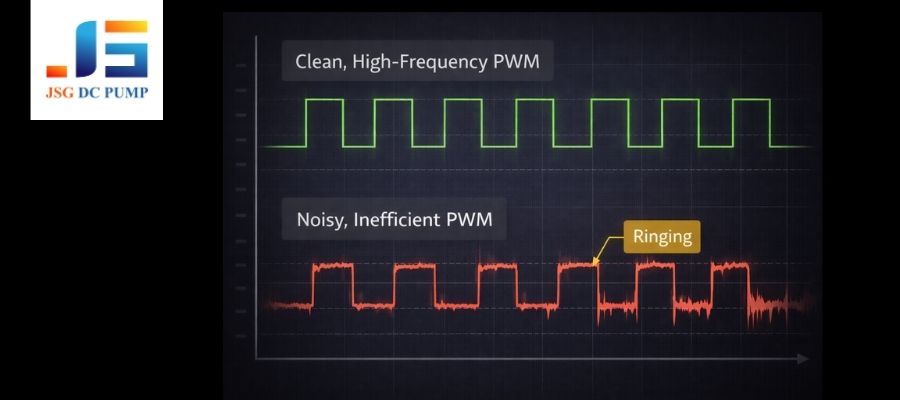

An oscilloscope showing a clean PWM signal versus a noisy, inefficient one

An oscilloscope showing a clean PWM signal versus a noisy, inefficient one

This is a more subtle issue I see. An OEM will choose a great low-speed pump but drive it with a very basic, low-frequency PWM controller. This “hard” switching can cause extra electrical noise and vibration, which translates directly into waste heat in the motor windings. Implementing a soft-start routine, using a higher PWM frequency (e.g., >20kHz) to reduce electrical harmonics, or adding current limiting in the driver software can make a huge difference. These strategies smooth out the power delivery, reducing electrical and mechanical stress on the motor. The result is a cooler, quieter, and more reliable system. The pump hardware is only half the battle; smart control is the other half. It’s a complete system problem.

Why Must Continuous-Duty Capability Be Proven, Not Claimed?

The datasheet seemed perfect, but the pump failed in your long-term testing. You’re frustrated because the specs were misleading. This is a common experience, and it’s why you must demand proof.

Claims of “continuous duty” on a spec sheet are meaningless without testing data to back them up. True capability must be proven through long-term run tests under your specific load conditions. Experienced manufacturers are cautious with this claim because reliability is proven, not just stated.

This is one of my core beliefs. A datasheet is a sales tool; a life test report is an engineering document. At JSG, when a customer needs a pump for a critical 24/7 medical or analytical application, we don’t just point to a spec sheet. We often set up a specific life test that mimics their exact use case—their pressure, their flow rate, their ambient temperature. We monitor the pumps for thousands of hours to validate their thermal stability and long-term performance. This gives our customers confidence that is based on real-world data, not just a marketing claim on a piece of paper. You should always ask a potential supplier: “Can you provide life test data for this pump under my specific load conditions?” Their answer will tell you a lot.

Conclusion

Continuous operation is a system-level outcome, not a motor feature you can buy. For small brushless pumps, look for low speed, quiet operation, and proven thermal stability under load.

If you are developing a 24/7 system and need support in evaluating real continuous-duty brushless DC air pumps—including load definition, thermal behavior, and long-term reliability testing—JSG DC PUMP provides engineering-level consultation and validated pump solutions for OEM applications.

For technical discussion or project evaluation, please contact:

admin@dc-pump.com